Do children need to know how to write?

Native human writing as the exception rather than the rule

We ran this debate years ago when it became clear that keyboards were our interface with the future. How could a child who can’t write a note survive, we asked? The argument goes on, but the truth is that we don’t communicate with the physically written word.

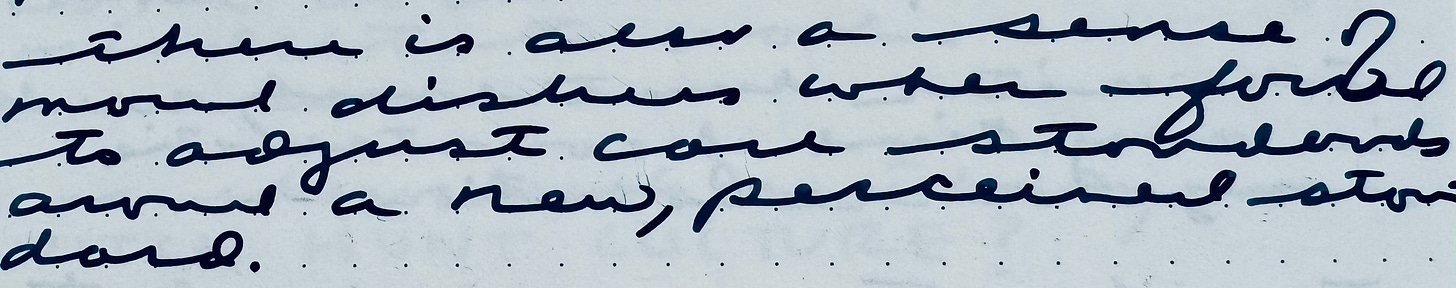

In my leadership role in Austin I’ve been using personalized handwritten notes with my colleagues — a special touch when things are done that deserve attention. In a blind moment recently I jotted a thank-you in cursive (using The Palmer Method, of course) and left it at a young doctor’s workstation. I felt less good about myself when I discovered that she couldn’t read it. She had to roam the hospital consulting all kinds of people to figure out what the hell I had said. She ultimately sought translation from one of our senior medical staff coordinators — A woman of a rare, wonderful vintage.

I now write my personalized messages in a blocky, computer-like print legible to most everyone.

But I digress.

Chat-GPT raises the next-gen question: Does a school-age student need to know how to write a sentence? Or is the skill instead knowing how to shape a prompt? And if the prompt doesn’t generate the copy that matches what we want to express, how do we then massage the input to deliver what most matches what we want to say?

I’m concerned that this will become the skill. The creative act may be understanding how to best manipulate the machine to shape what matches our wishes. Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms In the February 2024 Harvard Business Review use the term duet to describe the art of working collaboratively with AI systems.

Of course, the argument around Chat-GPT frames writing as a transactional thing where the end result is all that matters. I view writing like Joan Didion who suggested, “I write entirely to find out what I'm thinking, what I'm looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.” E.M. Forster similarly remarked, “How can I tell what I think till I see what I say?”

So the process of writing needs to be considered independent of the output. This may be the strongest argument for learning to write a sentence.

What about corresponding with one another? Well, we stopped ‘writing to one another’ a long time ago. Instead, we've evolved a kind of microstyle that matches the spaces we use to connect. So for exchanges in constrained spaces like Twitter or text, you don’t need to know how to write a sentence. Truncated phrases and abbreviations do the trick. Auto-correct and phrase completion amount to a kind of prompt response. Just start typing and your device finishes for you. ROTFL.

So like it or not, how we express ourselves is increasingly mediated by artificial tools. And how young people understand these tools will become at least as important as what I understand in shaping this very sentence on Ulysses. And like organic food or Instagram pictures that claim 'no filter,' I suspect we'll see the emergence of all natural, human-generated content. Native human writing will carry its own nostalgic value over time.

It wasn’t hard watching cursive disappear. It’s harder to see human-generated sentences become the exception rather than the rule.

This letter is human generated and untouched by Chat-GPT. The image is a cropped screen grab from my freerange journal.

I believe that just having cursive writing is not enough. You have to take a calligraphy course. It's even good for developing motor skills and coordination.