The End of Medical Credentialism?

How AI is unbundling medicine and surfacing 'high agency' doctors

Thanks for opening. I had a good time with this edition — the end of credentialism was fun to think through but there are still a lot of unanswered questions in my head. And a couple of interesting finds down below…

Dispatches

During a conversation with my friend Bhargav Patel, medical director of Sully AI, he floated a theory about the dissolution of many of the AI scribe companies (126 exist, by one count). So I had him on Freerange MD for an update on Sully AI and to expand on his dismal scribe outlook. It’s a 15 minute commitment — I might do these as impromptu, short conversations more often.

I host on Spotify’s Megaphone platform, so I think you should be able to listen to the episode right here. Hopefully.

The End of Medical Credentialism?

How AI is unbundling medicine and surfacing high agency doctors.

A recent piece in the Wall Street Journal caught my attention. It argues that AI is a boon to what author Andy Kessler calls high-agency people — that’s a next-gen kind of person who acts without waiting for permission. With tools like ChatGPT, Replit (which is very cool, btw), and Copilot, ambitious folks can do wild things that once required years of schooling.

It got me thinking: How will this energy impact medicine?

The hang-up is that medicine has always been about credentials. We’re a system built on hierarchy, licensing, and long training arcs. You don’t get to act until The Guild says you can. Medicine has historically stood as the anti-startup: a system built around risk aversion and slow, heavily credentialed access to participation. But it worked. It protected patients and preserved public trust. It gave us professional rigor and identity.

As background, credentialism is when we rely on formal qualifications or certifications to determine whether someone is permitted to undertake a task, speak as an expert or work in a certain field.

But AI doesn’t care about credentials. It cares about outcomes. And increasingly, so do we as patients and physicians.

Unbundling the Physician

Across the healthcare landscape AI is eviscerating the doctor into her constituent professional organs. So, essentially these pieces of doctoring can be automated:

Documentation. Clinical documentation is being handled by ambient scribes like Suki and SullyAI. These are systems that can generate a note and don’t require doctors. Or even humans (except the patient, of course)

Triage. First-line triage and diagnosis is emerging through LLMs trained on the medical corpus. Tools like Glass, SullyAI, and Hippocratic AI are building agentic models that mirror the core intake work of primary care.

Education. Medical education is being restructured in real-time by learners using GPT-tutors, board-style case generators, and sim engines that sounded like science fiction just a coupla years ago.

Remote monitoring. While not new, remote monitoring compounded by AI feedback loops is definitely new. And it’s turning patients into self-directed health actors without touching the health system. It’s what the original quantified-self pioneers could only imagine 15 years ago.

These aren’t hypotheticals. They’re live signals showing us a trend: The leverage is shifting towards individuals — patients and doctors.

A New Kind of Competence

Here’s a short, and very broad, history of medical education:

Past few hundred years: first get trained, then act.

Now: act, and train as you go. AI closes the loop in real time.

That doesn’t mean we throw out licensing, standards, or accountability. But it does mean we have to ask: what exactly are we credentialing for?

If a non-physician founder builds a diagnostic agent that outperforms your clinic’s intake process, what’s more important: the MD behind the idea, or the outcome it produces?

If a med student can master clinical reasoning faster with GPT-5 than through traditional rotations, do we still call that “cheating the system”? Or is it just a better system? This last example has teeth and it’s going to turn traditional meded on its head.

The High-Agency Physician

This is the other side of the story. And what Andy Kessler was referencing in the story.

Because it’s not just founders and tinkerers being empowered it’s us. AI gives physicians a new forms of leverage. High-agency doctors can now:

Build tools instead of waiting for them (and complaining about them).

Bypass institutional red tape.

Redesign their own workflows, practices, and value.

The physician of the future may not be the one with the most letters behind their name, but the one most willing to act, build, and lead in a changing system.

This almost takes us back to the early 20th century when doctors tinkered with things and created solutions.

Like the dawn of the internet -- on steroids

All of this reminds me of the early days of the internet. We all got access to the ‘printing press’, so to speak. Back then there were high-agency docs as well. But the only thing we could leverage was our voice. So, this new kind of AI maker economy feels like an extension of what initially began on platforms like Blogger and Wordpress.

What Still Matters

Let the hate mail roll … but this isn’t a call to eliminate credentialed physicians and elevate LLMs. Credentialing still matters, especially where accountability, ethics, and human judgment are involved. But we should distinguish between the sacred space where we want a doctor-in-the-loop and what’s just 20th century structural habit.

In other words, what will we turn over to agents, LLMs and others, and what will we insist be what I call the carbon constant, the thing we always need to be in the loop on.

In 2013 I wrote about medicine’s culture of permission — that is, the tendency to only do what you feel you are allowed to do. Remember that when I wrote this I was referencing content creation (social, writing, video creation) and public presence.</p>

Going forward, the conversion of medical information into knowledge and knowledge into wisdom can only happen in a culture of participation. In the emerging networked world, we are all individuals endowed with unique skills, abilities and gifts. The unique mindsets and views that define us will allow us to offer something that was never before available.

No truer words now. They’re just applied to new, powerful widgets.

Sooner rather than later, AI is going to make the medical profession very uncomfortable. And if you’re not uncomfortable with what’s happening, you’re asleep at the wheel. Seth Godin has suggested, discomfort is the feeling we all get just before change happens.

And the docs that thrive in this next chapter will be the ones who know how to seize the moment.

————

Signals | Ideas

The most important figure in medicine

This post from Morgan Cheatham on LinkedIn is one of the most powerful things I’ve seen in a while. He describes this figure as one of the most important in medicine.

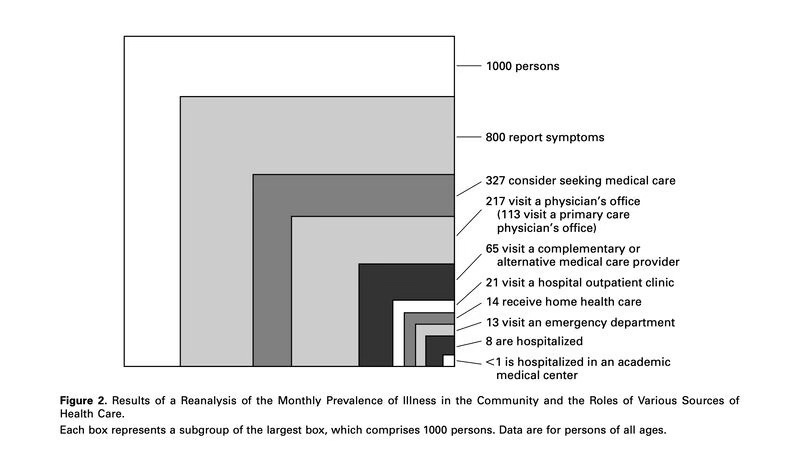

Published over two decades ago in NEJM, “The Ecology of Medical Care Revisited” captured a persistent truth: of every 1000 people, 800 report symptoms each month. 327 consider seeking care. 217 actually do. Just 8 are hospitalized. Fewer than 1 reach an academic medical center.

Most care begins—and ends—outside the walls of formal institutions. Yet our medical system continues to concentrate resources at the narrowest end of the funnel.

He goes on to suggest that AI might allow us to reach patients where they’re at and long before they ever hit an academic medical center. | LinkedIn

The Generalist-Specialist Paradox in Medical AI

Provocative editorial/essay I found this week.

AI now outperforms specialists at narrow tasks like EEG interpretation—but struggles to match generalist physicians in real-world clinical reasoning. In a recent editorial Dr. VL Murthy from U Michican calls this the generalist–specialist paradox in AI. And it has major implications for how we train clinicians and deploy these tools.

If AI continues to excel in narrow domains but falters in broader reasoning needed for primary care, we may need to rethink what “intelligence” means in medicine—and who (or what) we trust at the bedside.

I suspect this paradox is temporary. It’s purely a function of where we are at with these models. Specialist domains are more structured and easier to benchmark and train. The generalist stuff is messier and really contextual. | NEJM AI

Thanks for reading and please pass this along to someone who might be interested.

From your perspective, where does "Ethics" fit in? Is everything we do in Medicine about a measurable outcome?

This article obviously cannot lean into all the intricacies of medical practice and there is little doubt AI will be implemented in some form, but consider what we are seeing now: the cut and paste approach which at best preserves data, but too often perpetrates errors. Will AI be able to sort those issues out, especially in "translating" what a physician or practitioner says or does into verbiage? I can see real advantages, especially given some of the deplorable writing skills physicians display, but will AI actually transform something into "what it is not"? I do not believe you even wished to drill down to this kind of detail, dealing as you are at 50,000 feet, but as you also know, what happens on the ground is what matters to the people involved.

I have long thought that primary care is the most intellectually demanding field in medicine, and it requires the biggest skill set, especially in the psychosocial realm.